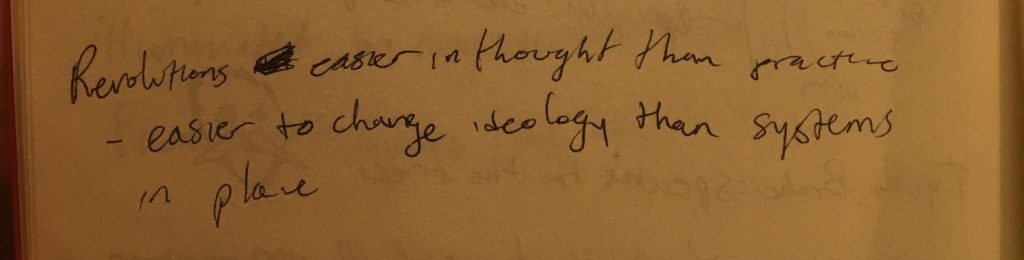

A revolution consists of intentional changes placed upon an institution that cannot reform itself, often resulting in a shift in thought. The institution is any system that holds some power over others. These changes are completely new to the institution and different from anything that has previously been done; if they are not, it would be easy for the institution to fall back on its old ways altogether. Oftentimes, these changes are placed upon the institution by a group of people rather than an individual, as revolutions require a variety of perspectives to enact. A revolution, however, is not just any systemic change – it is systemic change that lasts and prevents the institution from returning to its old ways.

I will use Dr. Robb’s “cluster method” of definitions to describe revolution. Something that satisfies most or all of the conditions above is a “revolution”; something that only satisfies one or a few of these conditions is “revolutionary.”

A revolution consists of intentional changes placed upon an institution that cannot reform itself, often resulting in a shift in thought.

Revolutions are similar to reform, but not quite the same. Reform is more simple and often easily happens within an institution. Kuhn, however, describes that revolution must occur from outside the institution. “Political revolutions aim to change political institutions in ways that those institutions themselves prohibit.” (274) Revolution is too radical to occur within the system it attempts to change.

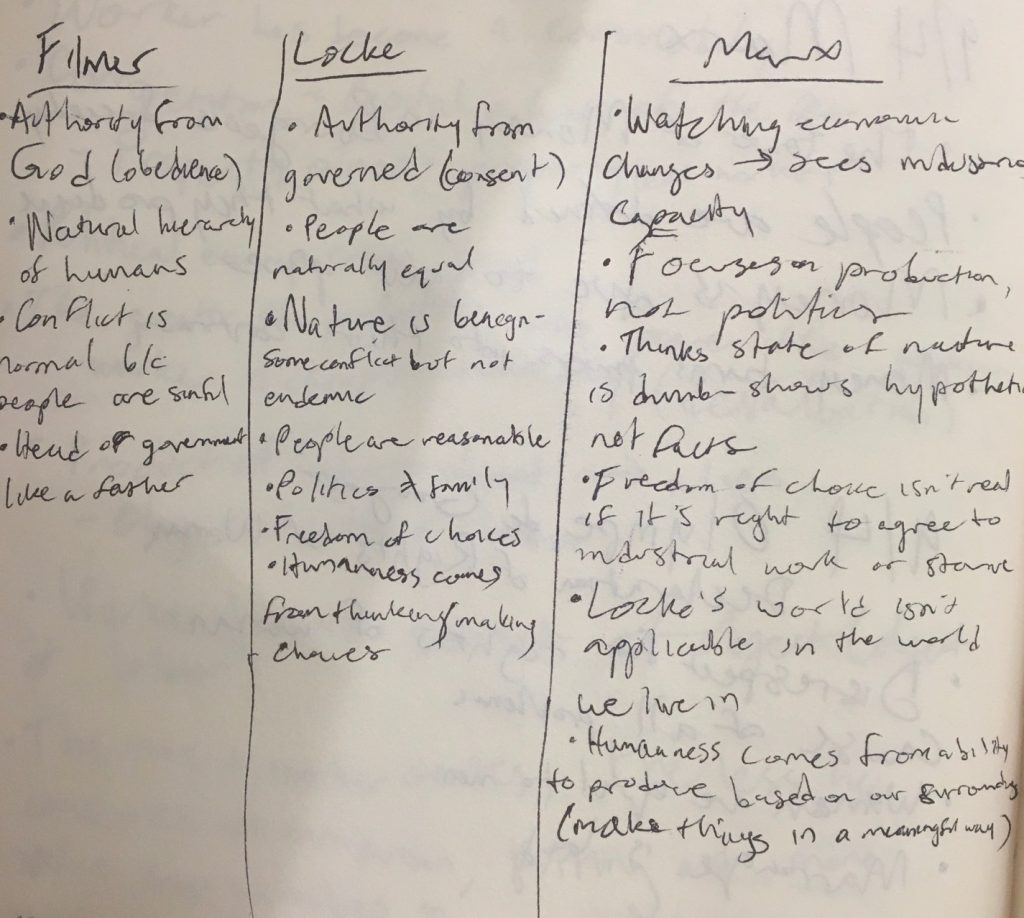

Boersema described Kuhn’s view of the Scientific Revolution, explaining that “change and progress in science is a matter of the replacement of paradigms,” (266). The shift of a paradigm creates a new way of thinking. Once a widespread change in thought has occurred, it is difficult to revert back to the old way of thinking, which makes it difficult to reverse the changes a revolution brings.

In Unit 8, we studied the The Red Army Faction (RAF), a militant left-wing organization in Germany in the 1970s. This group resisted the government because it believed government officials were remnants of the Nazi Regime of their past. Ulrike Meinhof, one of the leaders of the group, said “protest is when I say I don’t like this. Resistance is when I put an end to what I don’t like.” This resistance was an attempt at revolution, as the RAF wanted to change the German government, believing the government would not change itself without violence and threats.

A revolution consists of intentional changes placed upon an institution that cannot reform itself, often resulting in a shift in thought.

Revolutions are similar to reform, but not quite the same. Reform is more simple and often easily happens within an institution. Kuhn, however, describes that revolution must occur from outside the institution. “Political revolutions aim to change political institutions in ways that those institutions themselves prohibit.” (274) Revolution is too radical to occur within the system it attempts to change. Instead, revolutions that overhaul governments and political institutions are mostly enacted by those from “below.” “Below” in this sense does not refer to any one of a certain class or position, it refers to those who do not benefit from a power structure in place. A quote from Abraham Lincoln was featured in Lapham’s Quarterly, stating that America, “with its institutions, belongs to the people who inhabit it… they can exercise their constitutional right of amending it, or their revolutionary right to dismember or overthrow it.” (8). It only makes sense that those dissatisfied with an institution would attempt to radically change it. As the saying goes, “if it ain’t broke don’t fix it.” However, institutions often work well for some individuals, meaning this saying holds some truth, but revolution can be staged by the individuals hurt by the system.

Boersema described Kuhn’s view of the Scientific Revolution, explaining that “change and progress in science is a matter of the replacement of paradigms,” (Boersema 266). The shift of a paradigm creates a new way of thinking. Once a widespread change in thought has occurred, it is difficult to revert back to the old way of thinking, which makes it difficult to reverse the changes a revolution brings.

The institution is any system that holds some power over others.

In a poem written by Suheir Hammad, she lists stereotypical portrayals of women of color that she does not want to emulate, “not your harem girl geisha doll banana picker pom pom girl pum pum shorts coffee maker…” (64). Hammad describes the ownership that colonizers feel they have over the colonized, and the boxes that they are put into. These boxes are all roles of servitude to their oppressors, and describes the power imbalance. Rejecting these stereotypes, Hammad is committing an act of resistance, possibly an act of revolution.

These changes are completely new to the institution and different from anything that has previously been done; if they are not, it would be easy for the institution to fall back on its old ways altogether.

In Unit 4, the graphic novel March portrayed the peaceful protests of the Civil Rights era. These peaceful protests are revolutionary, as in many conflicts in American history, violence is used on one or both sides. The peaceful resistance taken on by the Freedom Riders, therefore, is an act of revolution; the method by which they were making change was new to the institution.

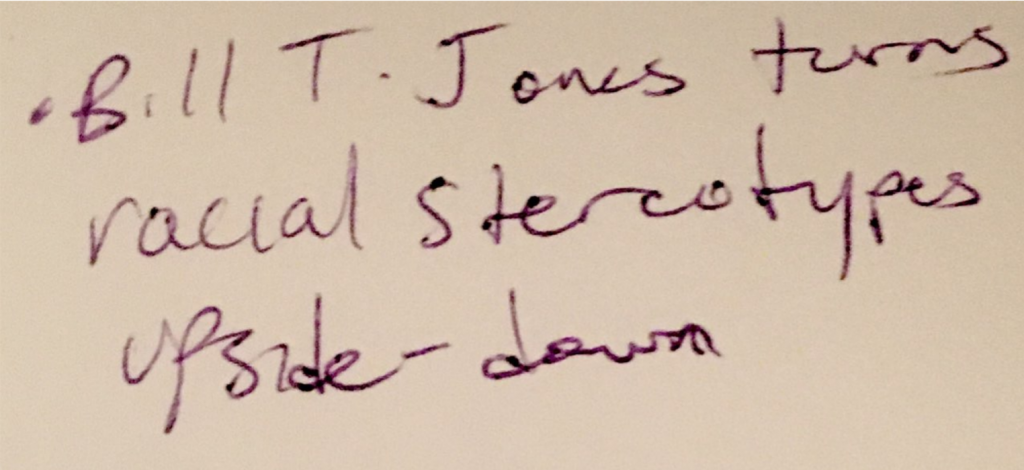

In Unit 5, Bill T. Jones’s Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land is revolutionary storytelling of Harriet Beecher Stowes’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Nereson argues that Jones portrays “four clear departures from Stowe’s Eliza,” (178). Stowes’s characterization of Eliza in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the “institution” in this case, was very static – she was solely seen as a mother figure. The original portrayal of Eliza and other characters in the novel fed into racial stereotypes that exist to this day. Bill T. Jones brings a completely new presentation of the story to the stage, with five different Elizas. Jones’s show can be considered a revolutionary act, as it brought a new point of view to the narrative.

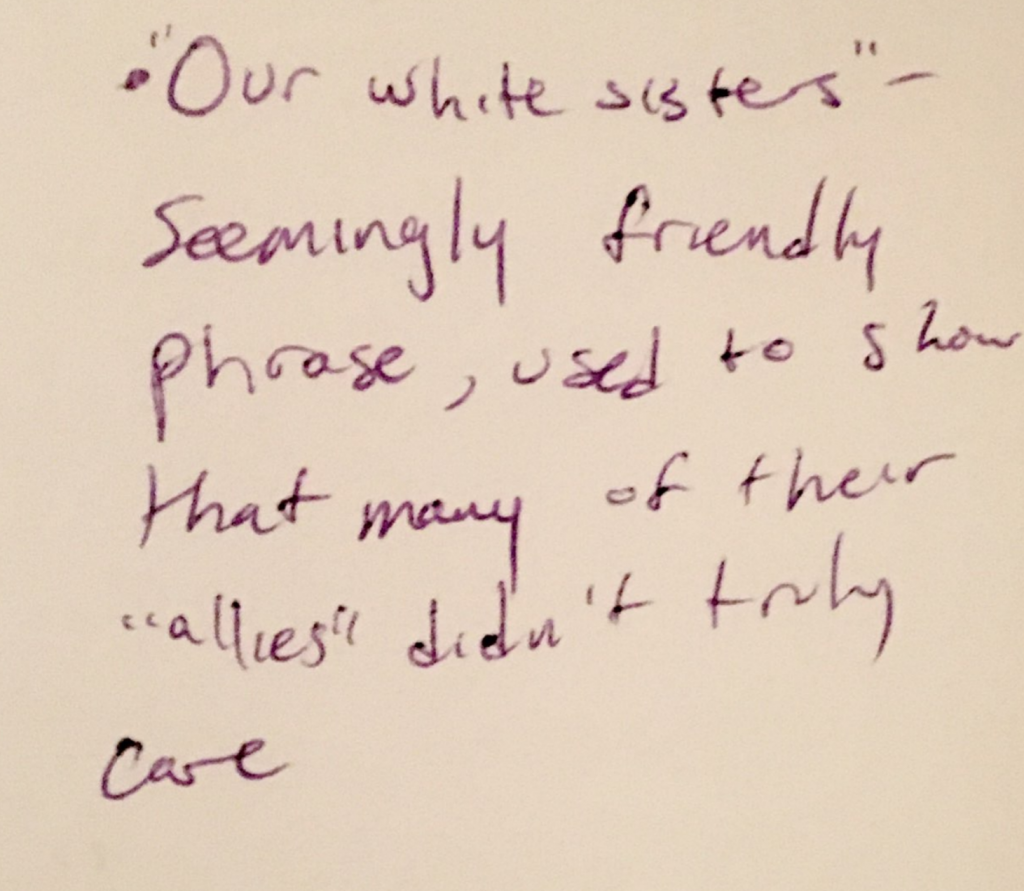

Nonrevolutionary acts can masquerade as revolutionary by individuals who want to appear as if they are making change, but are not willing to challenge the institution. This is described in Carillo’s poem, as she says, “our white sisters radical friends should think again. Our white sisters radical friends love to own pictures of us… reading books from literacy campaigns smiling.” (Carillo 63) This is a critique of those who like to think that they are making change and committing revolutionary acts, but really are not making much of a difference. The literacy campaigns are a step in the right direction, but the women are refusing to address issues mentioned earlier in the poem regarding socioeconomic inequality, a much larger issue within the institution.

These changes must be new to the institution to prevent leaning on the past. Davis mentions the “definition of neoliberalism: the flawed assumption that history does not matter.” (Davis 169) This neoliberalism creates, in effect, an anti-revolution: refusing to learn from the mistakes of the past prevents revolution in the future. Since we are immersed in the institution, we cannot let go of the paradigms we have learned to be true unless we recognize how we got here with acknowledgment of history. Not letting go of our paradigms leads to a lack of revolution.

Oftentimes, these changes are placed upon the institution by a group of people rather than an individual, as revolutions require a variety of perspectives to enact.

“Scientific revolutions are inaugurated by a growing sense, again often restricted to a narrow subdivision of the scientific community, that an existing paradigm has ceased to function adequately.” (Kuhn 274) The narrow subdivision within the scientific community is a group that recognizes the institution is not functioning. With multiple people in this group, they can work together to enact change.

In Unit 6, we discussed the connections between traditional sciences and traditional humanities. In Kandel’s work on scientific reductionism, he says “to advance human knowledge and to benefit human society, [C.P. Snow] argued scientists and humanists must find ways to bridge the chasm between their two cultures.” (3). In effect, he is saying that no one individual can entirely change the world – individuals must work together to make a change. The variety of perspectives and respect for each person’s expertise allow for new methods of thinking that can encourage a revolution; a revolution cannot occur in a vacuum of one discipline. A group of individuals with varying strengths is necessary to create a successful revolution. This allowed for a revolution in art analysis through “scientific reductionism,” in which art can be examined on a small scale to explain its appeal to us, as humans.

A revolution, however, is not just any systemic change – it is systemic change that lasts and prevents the institution from returning to its old ways.

This is the trickiest part of the definition, as it is impossible to tell if a revolution will last – any revolution could end with the institution reverting to its old ways, or it could end with another revolution taking over. For example, the Civil Rights Movement could be seen as a revolution – it aimed to change the structure of the United States. While America was theoretically desegregated, however, the institution found ways to fight against this revolution with policies such as redlining. In addition, many racist people did not change their beliefs during the Civil Rights Movement – in their eyes, only the laws had changed. The Civil Rights Movement could therefore be classified as a revolution, but not a fully successful one.

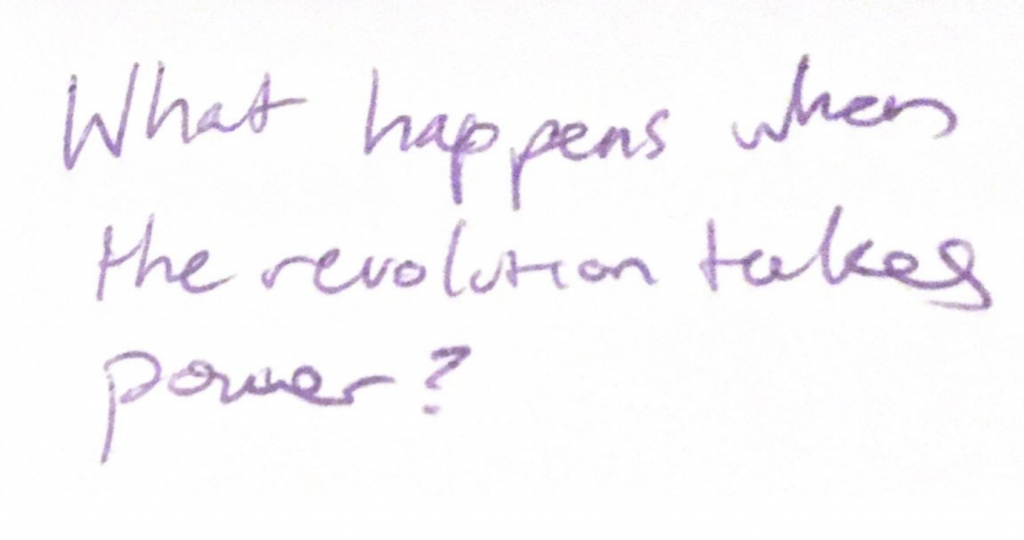

In Unit 7, we discussed the Soviet Union and the implications of a revolution once it takes power. We discussed the great suffering of many Russian people throughout Stalin’s purges. We read Sophia Petrovna, a novel by Lydia Chukovskaya depicting the struggles of the titular character after her son senselessly disappears. Although the Russian Revolution was definitively a revolution, the communist ideology of those who took power created a revolution in common ideology and beliefs in the Soviet Union. Many people suffered the same fate of random disappearance; the impression that this leaves on the nation’s psyche cannot be undone. These mass killings and disappearances enacted by Stalin were revolutionary in their impacts on countless Russian families and citizens.

Even if the revolution only changes ideology and beliefs, and does not overhaul a government or tangible system, it can still be considered a revolution. This is because, in these cases, ideology and beliefs can be considered the institution. In Lapham’s Quarterly, Yasmine El Rashidi describes her experience in the Egyptian Revolution. The Egyptian Revolution certainly left the governmental institutions with lasting change, but El Rashidi says in her article that her “relationship with [Cairo], with a culture, with [her] home, has forever been changed.” (145). The events of the Egyptian Revolution were not just events that changed a government, they changed El Rashidi’s connection to the city in a way that can never be reversed.

Citations

“All Men Would Be Tyrants If They Could” in Lapham’s Quarterly, Spring 2014, Vol. 7 Issue 2, p88.

Boersema, David. Philosophy of Science. Pearson Education, Inc., 2009.

Carrillo, Jo. “And When You Leave, Take Your Pictures With You.” This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, State University of New York Press, 2015.

Davis, Angela. “Recognizing Racism in the Era of Neoliberalism” in The Meaning of Freedom and Other Difficult Dialogues, City Lights, 2010.

Kandel, Eric R. 2016. Reductionism in Art and Brain Science : Bridging the Two Cultures. New York: Columbia University Press. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.davidson.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1341916&site=ehost-live.

Kuhn, Thomas. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Lewis, J., Aydin, A., Powell, N., & Small Press Expo Collection (Library of Congress). (2013). March: Book One.

Nereson, Ariel. Counterfactual Moving in Bill T. Jones’s Last Supper At Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land. American Society for Theatre Research, 2015.

Rashidi, Yasmine El. Lapham’s Quarterly , Spring2014, Vol. 7 Issue 2, p144-148, 5p